- Home

- Brandon Mull

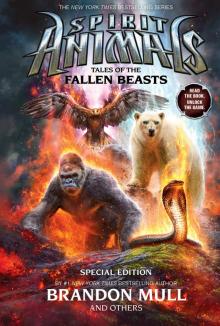

Tales of the Fallen Beasts

Tales of the Fallen Beasts Read online

Contents

Fallen Beast Symbol

Greencloak Letter

Quote Page

Title Page

Map

Halawir

Unleashed

Rumfuss

The Trunswick Blade

Suka and Arax

A Chill Wind

Kovo

Rebel Bond

Gerathon

Betrayal

About the Author

Online Game Code

Sneak Peek

Spirit Animals Game

Copyright

THERE WAS A TREMENDOUS BRILLIANCE, LIKE A BLINDFOLD had just been pulled away from his eyes, and for a moment Halawir felt nothing but the sting of too much light everywhere. He was consumed by a purple radiance, the whole world like the penumbra of the sun.

And then the rest of his body caught up to his eyes. He was joyfully aware of the wind in his feathers. He could taste the salt spray and smell the raw, endless sea pulsing below him. He heard the rush of the air as it parted to make room for his body.

He was soaring.

He pumped his wide wings up and down, enjoying the way they pushed the air around, currents tense and smooth as water, the tips of his wings brushing lightly against the sky. He stretched them out to their fullest span, nearly seven feet, so that he could see the sun glinting on the blue and gray of the feathers under his wings.

Halawir let out an exultant scream.

He was a Great Beast, and king of these skies.

Fast and focused, majestic wings now flush against his body, Halawir reached the apex of his flight and turned to dive down. A seagull crossed his line of vision, and he lunged at it playfully.

Of course, the seagull didn’t know that Halawir was simply feeling out his strength—it assumed it was destined to be dinner. It flapped away as fast as it could, squawking wildly. Halawir’s eyes squinted in an avian smile. If he were in the mood to hunt, that seagull wouldn’t have a chance. But he let the bird go.

Now he saw an ocean of Erdas spread out below him. He still didn’t know where he was, just that it was good to be here at all—to be back.

He zipped down farther still, skimming along the surface of the foamy sea—following the curves and crests of the waves but never getting wet—then up over a sea trader’s sleek boat—

The next moment, a heavy net fell over his head. His wings tangled up in the rope and he came crashing down, landing on a hard surface with an undignified thud. He tried flapping his wings, squirming to get free of the net, but he only got more and more ensnared. Casting his eyes about wildly, Halawir could see that he was on the deck of the boat. Well-worn wooden planks slid beneath his talons as he scrambled to get his footing back.

“You got him!” exclaimed a high voice, followed by footsteps running toward him. “I can’t believe it! He’s incredible.”

It sounded like a child. Halawir’s panic threatened to overwhelm him, but as the pumping in his heart subsided, he could see the young girl crouched next to him. She looked to be about eleven. Her skin was brown and her hair was pale, as if the sun had both toasted and bleached her.

A deeper voice spoke. It was a man dressed simply but neatly, with the same dark skin as the girl. “Cordalles, you did it! You’ve summoned a spirit animal!” The man paused, and Halawir could hear him trying to control the pride in his voice. “A bird is the perfect creature for a seafarer like you.”

“That’s not just a bird,” snapped the woman standing next to him. “Did you see its wingspan? Look at its hooked beak. It’s an eagle, Imari.”

“An eagle?” said the girl, Cordalles. Halawir turned his yellow eyes to peer at her. “It can’t be an eagle,” the girl continued. “Everyone knows that you can’t summon an eagle as a spirit animal, because Halawir—” She bit off the end of her sentence.

“Halawir,” the man echoed. “The Great Beast?”

“The betrayer,” said the woman sourly.

“This can’t be him,” the girl said, but Halawir could hear the doubt in her voice. She didn’t sound all that happy. Well, that made two of them.

Cordalles craned her neck to get a better look at his face through the net. Halawir pumped his massive wings again in protest, but the heavy net didn’t allow him to gain any traction in the air. He let out a screech of rage. It was absurd to be kept trapped by a bunch of seafaring nobodies who probably couldn’t even spot a fish flashing beneath the waves from three hundred meters away.

Halawir had come close to ruling all of Erdas alongside Kovo and Gerathon. He had held the shining talismans in his talons, had seen the arrogant Greencloaks run screaming from their silly castle. The war had turned against him and his allies in the end, but Halawir knew what it was to be one of the mightiest creatures on the face of Erdas. He knew what it was to make people tremble. And now—

He narrowed his yellow eyes at the girl to show that they were not friends, that they could never be friends. But she was ignoring that very clear signal. In fact, she reached her pointer finger out to lightly touch one of the blue-gray feathers under his mighty wings.

“He is beautiful,” she said.

“Careful, Cordalles,” the girl’s mother warned, and rightfully so.

Halawir would certainly have pulled away, if he could. Would have happily clawed her eyes out, if he could. But he was immobilized, with no choice but to wait as she ran the tip of her finger along the length of his feathers, as if he were some little fluffy-headed chick, too young and weak and stupid to know how to fly.

Still, as she stroked his glossy feathers, he felt himself weakening. It was like some tiny yellow chick was there inside him, cracking out of the shell of his heart and leaning in toward Cordalles.

It surprised and scared him, the tentative feeling of connection between them. The hours the girl spent at the top of the boat’s rigging, the sea flying by her and the wind whipping her hair into a froth, left a scent of the sky on her. That was something they shared. He sensed that she loved the feel of the wind in her face, like he did.

But he didn’t like this weak spot in himself. She was holding him prisoner.

That could not be forgiven.

He would not be some girl’s spirit animal, dependent on her whim. He would not subject himself to the passive state. Maybe that was fine for slow-moving Jhi, or a more common creature, but not him.

Halawir used the power of his strong will to turn himself away from the spark of their bond. He would ignore it until, like any burning ember with no fuel, it would fade out and die.

As he had sat there like a dumb cow, dazed by the touch of the girl’s finger, the older woman had been approaching. Now, all of a sudden, she reached under the net and pulled on Halawir’s leg.

Again, he fought, the sudden softness forgotten, this undesirable intimacy stirring him to intense anger. He thrashed his wings and neck and legs, but she had him, she had his delicate leg. He tensed his talons, hoping for at least one good scratch on her tough hide, and when that didn’t work he curved his body around and dove in with his beak for a peck. He tasted blood. She screeched and pulled away, but not before she had slipped a little knotted rope up over his foot and tightened it around his leg.

“That beast attacked me!” The woman brandished her arm in front of her. Halawir saw the gouge his beak had made in her fleshy forearm. Good.

“Mother!” the girl cried. “Are you okay? I’m so sorry! I didn’t know he would—Halawir, how could you do that?”

“I’m fine. At least I got the leash on so we can get him under control.” The mother’s mouth twisted into a grim smile and she handed the other end of the rope to the girl. Then together, the woman and the man untangled

the net and lifted it away from Halawir.

The second it was gone, he took off into the sky.

He wasn’t stupid; some part of his mind remembered that he was leashed, but his instincts were connected directly to his muscles, and he reacted long before his mind was able to chime in with some helpful advice. His heart soared and his wings followed, the instinct alive and immediate. Like an arrow shot into the sky, he took off—until he reached the end of the cord.

It yanked back on his leg, hard, and he boomeranged down in a tumble of feathers and fury onto the deck.

“Shhh,” said the girl, his captor, the other end of the rope twisted around her wrist. “Calm down.”

Calm down.

He was on a leash like a groveling pet, and she thought he was going to roll over and play along?

She looked up at the adults. “Isn’t he supposed to feel a bond with me?”

“It’s natural, when a spirit animal is first called, for the bond to be weak,” answered her mother. “It’s something that both partners must work on and cultivate. Something that the two will strengthen over the years. Usually.”

Halawir let out a cackling laugh and his feathers raised like hackles. He wouldn’t be working to strengthen this bond. He had no interest in becoming any closer with a sniveling child. He’d had enough bad experiences with children already. He shook out his wings, brushing off the memory of Meilin, Abeke, Rollan, and Conor. Those baby Greencloaks who had cost him, well, everything.

“Okay, we’ll work on it,” Cordalles said, only the hint of a question in her voice. “I’m sure that once we spend time together our bond will feel more, um … ” She coughed. “I’m sure there’s lots we can learn from each other, anyway. Lots he can teach me.” Her voice perked up with newfound enthusiasm. “Maybe soon I’ll be running across the deck of the boat as fast as though I had wings.”

Her father smiled. “Or maybe you could be our new lookout, once you have eyesight as powerful as an eagle’s. Relieve Bao of his night watch.”

“Yes!” Cordalles crowed. “And I’ll—”

“One step at a time, little sparrow,” her mother said, placing her hand firmly on Cordalles’s shoulder.

“You’ll see,” Cordalles said. She shrugged the hand back off. “And with Halawir to look out for me, you’ll let me go off on my own when we dock, maybe? Since he’ll be there to protect me. We’ll start working on strengthening our bond right away, won’t we, Halawir?”

It was a clear question that demanded a clear answer.

He unfolded his wings and gave one powerful beat to launch himself up. Hovering on the softest air current, he felt himself relax into the air. Floating lightly at the end of his tether, he positioned himself directly above Cordalles. He could see her parents standing close by her, and the ship’s crew looking on curiously from around the deck.

Then he loosened his bowels and pooped on her head.

An hour later, Halawir was sitting on a small perch in a cramped bunk in the depths of the boat. He had to hunch his shoulders up around his neck to fit his bulk inside the tiny room. There was a low ceiling that sloped up from an even lower wall. Only one round porthole showed a glimpse of the outdoors: a swinging view that flashed between sea and sky, sea and sky. Cordalles had just finished washing her hair in a bucket and was toweling it dry in the opposite corner of the room, as far away from Halawir as she could get, which wasn’t very far at all.

“I didn’t know Great Beasts had such great senses of humor,” Cordalles said, not laughing.

Halawir was aware that his form of objection had not been the most dignified, unfortunately. But in this instance, he hadn’t felt he’d had any avenues of complaint open to him other than this silent protest.

He could tell that Cordalles and her parents didn’t trust him. Well, that made them and every other human on the planet. His reputation was, at the moment, much more powerful than he was.

She took a deep breath. “You are my spirit animal, you know. I didn’t choose this any more than you did, but here you are. You’re as bonded to me as I am to you, so we should really make the best of it. Trust each other, and all that. Okay?”

She stuck her left arm out in front of her.

Halawir stared at her blankly. Was this some strange seafarer’s friendship ritual? No, thanks.

Then, with a start, he realized that she was holding out her arm for him to transform into a tattoo on her skin, the passive form of a spirit animal. Was she out of her mind? He let out a harsh cry of derision. She was a fool and had learned nothing about him if she thought that he would willingly submit himself to her.

He turned his back to her haughtily and closed his eyes, but she kept talking to him.

“You know my parents don’t like you. They don’t trust you at all. To tell you the truth, they don’t trust me much, either.” She sighed. “Whenever we dock, they never let me go off on my own to look around. We visit some of the finest cities in the world, all the largest ports in Erdas, and they never let me out of their sight! So, if it makes you feel any better, I know what it feels like not to be trusted.”

Halawir wished he could shut his ears as well as his eyes. For now he was a prisoner, stuck here in these oppressive quarters out in the middle of the ocean, but soon he would be free of these humans and their petty quarrels and concerns.

At least he wasn’t in danger at the moment. He would rest. Gather his strength. As soon as they approached land, he would make his escape.

Halawir kept his eyes firmly shut to the world until, at long last, he heard footsteps. A moment later, Cordalles’s mother squeezed through the low door to the room. She perched on the bunk next to her daughter and ran her fingers through the girl’s wet hair.

“I’ve been talking to your father,” she said in a low voice, as though Halawir couldn’t hear if she whispered. “We’re not quite sure what to do with this … with your … with Halawir.”

“What do you mean?” Cordalles said.

“Well, it’s unheard of to summon a Great Beast, except for the four heroes who stopped the Conquerors. We’ve spoken to all the sailors on the ship, but no one’s got a clue what it means, or what to do with him. We’re in luck, though. We’re heading through the Strait of Gibral toward Amaya, which means that Greenhaven, the home of the Greencloaks, will be pretty much on our way. Your father and I think we should stop there. Perhaps the Greencloaks will be able to give us some guidance. They spend their lives dealing with matters of these bonds. Someone there will certainly know what to do with it—with him.”

Cordalles furrowed her brow. “There’s nothing to do. He’s my spirit animal. Just like Juno has Freelam, or Bao has—”

“My sweet seagull, you must see that it’s not the same. This bird was one of the masterminds of the Devourer Wars. He’s smaller now, so I know it’s hard to believe, but he was once so huge that the Devourer rode through the skies on his back. This is the creature whose schemes and tricks cost thousands of lives. He even betrayed his fellow Great Beasts. I’m not sure that’s exactly the type of animal you want as your cabinmate.”

“We have a bond, though,” Cordalles said. “I can definitely feel it.”

Halawir almost choked. She was clearly lying through her teeth to her mother. He couldn’t help admiring her almost a little; she was very convincing.

He must have made a strange noise, because Cordalles’s mother started. Halawir wondered if she realized that he could understand every word she was saying.

She pulled Cordalles into her arms. “Just because you love birds doesn’t mean they’re all your friends. Look, I’m not saying you’ll need to be separated from him permanently. I just think we should get some advice from the Greencloaks, is all. It’s only a few days’ sailing out of our way. We’ve informed the crew of the slight change in route. They’re happy to be getting the extra pay.” She leaned down and kissed the girl on the top of her head. “Let your father and I decide what’s best for you, my sparrow.”<

br />

Cordalles shrugged her mother off. She straightened her narrow shoulders and looked right at Halawir. “You wouldn’t betray me, would you? You can feel that there’s something—something connecting us?”

Halawir closed his eyes against the intensity of her gaze.

They were taking him to Greenhaven, the home of his enemies.

For the very first time, he felt thankful that fate had brought him this girl.

He would finally have a chance for revenge.

Just then, the sack came down over his head.

Cordalles’s mother tossed him unceremoniously into a windowless cabin even smaller—if such a thing was possible—than the one Cordalles had originally brought him to.

She stood watch from a safe distance while a burly sailor tied his leash to a post and placed bowls of water and dried meat near him.

Finally, the sailor left the room, giving one last suspicious glance to Halawir as he left, and the woman smiled in faux apology.

“I know you’ll understand,” she said. “I can’t let my daughter become too attached to you. It’s for her own good. Yours too, probably. What if a true bond developed? It would be all the worse when we would eventually have to separate you two. Because my daughter is not going to spend her life with a traitor as her spirit animal. She deserves better than that.” Saliva flew from her lips as she spat the last words at him. Perhaps she was trying to shame him, but Halawir didn’t care about that at all. “We’ll leave you with the Greencloaks,” she continued. “You can be their problem.”

So she’d been lying, too. Halawir couldn’t care less about being separated from Cordalles, either. The only thing that mattered to him was that the ship continued on its course toward Greenhaven.

The woman left the room. He could hear the sound of the door locking behind her, followed by running feet, and then, faintly, the sound of someone crying. He perked up his ears. Eagles were known for their keen eyesight, but his hearing wasn’t bad, either.

“—have to let me in.” It was Cordalles, sobbing and pleading with her mother. “I’m telling you, he’ll listen to me. Don’t you trust me at all?”

The Candy Shop War

The Candy Shop War Rise of the Evening Star

Rise of the Evening Star Death Weavers

Death Weavers The Candy Shop War, Vol. 2: Arcade Catastrophe

The Candy Shop War, Vol. 2: Arcade Catastrophe Chasing the Prophecy

Chasing the Prophecy Fablehaven

Fablehaven Dragonwatch

Dragonwatch Time Jumpers

Time Jumpers Seeds of Rebellion

Seeds of Rebellion Keys to the Demon Prison

Keys to the Demon Prison Secrets of the Dragon Sanctuary

Secrets of the Dragon Sanctuary A World Without Heroes

A World Without Heroes Master of the Phantom Isle

Master of the Phantom Isle Grip of the Shadow Plague

Grip of the Shadow Plague Crystal Keepers

Crystal Keepers Champion of the Titan Games

Champion of the Titan Games Sky Raiders

Sky Raiders Dragonwatch, Book 2: Wrath of the Dragon King

Dragonwatch, Book 2: Wrath of the Dragon King Dragonwatch, vol. 4: Champion of the Titan Games

Dragonwatch, vol. 4: Champion of the Titan Games Legend of the Dragon Slayer

Legend of the Dragon Slayer Chasing the Prophecy (Beyonders)

Chasing the Prophecy (Beyonders) Fablehaven2-Rise of the Evening Star

Fablehaven2-Rise of the Evening Star Candy Shop War

Candy Shop War Wild Born

Wild Born Wrath of the Dragon King

Wrath of the Dragon King Spirit Animals Book 1: Wild Born

Spirit Animals Book 1: Wild Born Fablehaven1-Fablehaven

Fablehaven1-Fablehaven Tales of the Fallen Beasts

Tales of the Fallen Beasts Dragonwatch: A Fablehaven Adventure

Dragonwatch: A Fablehaven Adventure Tales of the Great Beasts

Tales of the Great Beasts